The Four Living Creatures and the Four Gospels:

The ancient biblical visions of the prophet Ezekiel can seem distant and mysterious, but the four living creatures he saw descending from heaven have a profound and enduring connection to our modern faith. For centuries, Christian thinkers have associated these creatures with the four canonical Gospels, a connection first established by the influential 2nd-century Church Father Irenaeus of Lyons. This powerful association not only helped solidify the authority of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John but also provided a clear defense against the proliferation of other “gospels” that were widely circulating. By understanding Irenaeus’s work and the historical context of his time, we can appreciate why the four gospels were affirmed as the foundation of Christian teaching and why this framework remains relevant today.

With Ezekiel on the Plain of Chebar

In Ezekiel chapter one, the prophet finds himself in captivity far from Jerusalem and as a result desperately seeks the face of God for understanding, comfort, and deliverance. Is that you? Are you in a “far off” place, spiritual and crying out for a shift, change, and deliverance? As with Ezekiel, these moments of despair and struggle can give birth to powerful insights and an understanding of God’s nature and His dealings with mankind. In Ezekiel’s case, in chapter one of Ezekiel, he experiences a profound vision of the glory of God descending from heaven in the form of what we would describe today as a mysterious engine, an organic being, or a hybrid, which at one point shows four faces. What those faces meant to Ezekiel in the immediacy of his situation, we do not know, but these four “living creatures” reappear in Revelation 4:7, thus emphasizing that Ezekiel is seeing far beyond the ancient context of his own life and the national life of Israel and the people in captivity. He is looking far into the future to a time when four messages come to us from divine inspiration in the form of the four Gospels.

The connection between the four creatures and the four gospels is found throughout Christian centuries and is not a new invention. The connection between the four living creatures described in Ezekiel 1:10 and the four gospels was first made by Irenaeus of Lyons in the late 2nd century. He made this association in his written work “Against Heresies” as part of an argument to show that there could only be four authentic gospels. Who was Irenaeus of Lyons, and why would he do this? Why would he insist there are only four “authentic gospels?” The assertion of only four authoritative gospels makes sense because if the gospels were multitudinous, then instead of four living creatures representing four authentic gospels, we would have a hideous chimera in the form of the many-headed hydra to describe the many, many purported gospels that cropped up in ancient times and indeed proliferate right down to today.

Who Was Irenaeus?

Before proceeding, let’s examine Irenaeus, as he is one of the earliest to suggest what we would call today “canonical” or authoritative gospels. He was also the first to connect the four gospels with the four living creatures of Ezekiel 1:10 and John 4:7.

Irenaeus of Lyons was a prominent Christian theologian and bishop of Lugdunum (modern-day Lyon, France) in the 2nd century. Born in Asia Minor (c. 130–202 AD), he is considered one of the most important early Church Fathers. His main work, Against Heresies, was a refutation of Gnosticism, a movement that claimed to have a “secret knowledge” (gnosis) passed down from Jesus to only a select few. Why would we concern ourselves even today with this “Gnostic” influence? Again, their concept of salvation was not squarely based on the person of Jesus Christ, but rather on supposed mystical knowledge imparted by Jesus, which, once acquired by a seeker, would constitute that individual’s place in the plan of redemption and render them “saved.” We don’t think that way today, do we? Well, ask yourself what the basic beliefs are you’ve been taught about Jesus and Christianity as a whole, such as the belief in the Trinity, heaven and hell, the necessity of water baptism, certain beliefs regarding eschatology, or the end times?

What if we DON’T believe in one or more of these things? Does that mean we aren’t going to heaven? A gnostic approach would insist that no, if you don’t believe certain doctrines, you DON’T get to heaven. Thus, the suggestion is that knowledge, mystical and secret, is the key to salvation, which poses a significant problem. Yet, at the same time, modern Christianity organizes itself around religious knowledge, doctrines, and beliefs. The early church fathers, if they could look at Christianity as we know it, would fairly accuse the church of today of widespread gnostic heresy. What is the answer? Knowledge doesn’t save us – JESUS SAVES US! It might be a good thing if a modern-day Irenaeus were to surface in modern times and speak out against these knowledge-based systems and denominations, bringing the church back to its foundation in Christ. That doesn’t mean that knowledge of the holy isn’t important – it is, but knowledge and theology (which should not be forsaken) are not the basis of our redemption.

Irenaeus’ Authority to Suggest Only Four Gospels

Irenaeus’s authority to declare that there were only four authentic gospels came from his unique position in the Christian tradition. He was a student of Polycarp, who, in turn, was a disciple of the Apostle John. Polycarp is important because, along with his contemporary Onesimus, they were among the earliest Christian leaders to possess and venerate the balance and preponderance of the books of the Bible we accept today as authoritative and genuinely passed down to us by divine providence. This connection between Irenaeus and Polycarp (again a direct disciple of John the Beloved) gave Irenaeus a direct link to the very first generation of Christians and a claim to have received the true apostolic tradition.

Irenaeus’s argument for only four authoritative gospels was not just personal; it was a defense of the public, verifiable, and universally accepted Christian tradition against the secret and fragmented teachings of the Gnostics. He argued that the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—were the only ones universally accepted by the churches around the world. These gospels were publicly known and their teachings were consistent, in contrast to the various Gnostic writings.

He pointed to the unbroken chain of bishops, from the apostles to his own time, who had preserved the true teachings and scriptures. By doing this, he asserted that the authority lay not in secret knowledge, but in the public, consistent tradition handed down through the church’s leaders and enshrined in the four gospels.

What is the Number of Competing “Gospels?”

Just how many gospels are there anyway? Based on scholarly research, ancient texts, and archaeological discoveries, a reasonable estimate is that dozens, and potentially over 50, purported gospels have been written or mentioned in historical sources. Why aren’t they included in the Bible? Because church councils (mostly in the early centuries) concluded that all but the four Gospels were spurious creations generated to support heretical claims, teachings, and groups, such as the Gnostic groups and many others. They fabricated these “pseudo gospels” claimed to have been written authoritatively by authors such as Thomas (Gospel of Thomas) and even Judas!

Many of these gospel pretenders no longer exist, being lost to history, but of the number that we know about, they include:

- The four canonical gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John).

- Around 20-30 significant non-canonical gospels, such as the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, the Gospel of Mary, and the Gospel of Judas, for which we have surviving texts or significant fragments.

- Numerous other gospels that are only known by name from the writings of early church fathers who condemned or referenced them, but for which no text has ever been found.

Many of these non-canonical works were written well into the 2nd, 3rd, and even 4th centuries, often reflecting specific theological viewpoints, such as Gnosticism, which were later deemed heretical by the mainstream church.

The history of the gospels is a complex topic, and there is a significant difference between the canonical gospels and the many others that were written. Here is a breakdown of some of the most prominent purported gospels.

The Canonical Gospels

These are the four gospels that were eventually accepted into the New Testament canon. While they are traditionally attributed to specific authors, modern scholarly consensus is that their actual authors are anonymous.

Gospel of Mark

Purported Author: The Apostle Mark, a companion of Peter.

Date: Most scholars date it to around AD 65–75, shortly after the destruction of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. It is widely regarded as the earliest of the four canonical Gospels.

Entered Christian History: Mark’s gospel was one of the foundational texts used by the authors of Matthew and Luke, indicating its early and widespread circulation. By the late 2nd century, it had firmly established itself as one of the four authoritative Gospels.

Gospel of Matthew

Purported Author: The Apostle Matthew, one of Jesus’s twelve disciples.

Date: Scholars generally date it to around AD 80–90.

Entered Christian History: The Gospel of Matthew was highly popular in the early church and was often seen as the primary gospel. Its use by early Christian writers, such as the author of the Didache, an early apostolic writing circulated among the churches around AD 95, demonstrates its early acceptance and authority.

Gospel of Luke

Purported Author: Luke, a companion of the Apostle Paul.

Date: Generally dated to around AD 80–90, or possibly slightly later.

Entered Christian History: As the first part of a two-volume work (Luke-Acts), this gospel was also well-known and cited by early church fathers. It was quickly integrated into the recognized body of gospel literature.

Gospel of John

Purported Author: The Apostle John, “the beloved disciple.”

Date: Most scholars date it to around AD 90–100, making it the last of the canonical gospels to be written.

Entered Christian History: Although written later, its unique theological perspective on the divinity of Christ ensured its quick and widespread adoption. It was a key text in the theological debates of the 2nd century and was defended by figures like Irenaeus.

Before going on to consider the “Non-Canonical Gospels,” let’s address the question as to why scholars consider even the four authoritative gospels as being written anonymously and at a much later time than traditionally thought. Scholars question the traditional authorship of the four gospels due to a lack of direct evidence, internal inconsistencies, and historical context. The four gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—do not name their authors within their texts. The names were added later, likely in the 2nd century.

Why Scholars Question Traditional Authorship

-

-

- Anonymity: The original manuscripts of the gospels are anonymous. The titles “The Gospel According to Matthew,” for example, were added later as a way to identify and distinguish the texts. This practice became standard in the late 2nd century.

- Internal Evidence: Scholars analyze the content of the gospels for clues about their authors.

- Markan Priority: The Gospels of Matthew and Luke appear to have used Mark’s Gospel as a primary source. It’s considered unlikely that an apostle and eyewitness (Matthew) would have heavily relied on the work of a non-eyewitness (Mark) for his own account of Jesus’s life. This suggests that the authors of Matthew and Luke were later writers who were part of a developing gospel tradition, rather than original disciples.

- Stylistic Differences: The Gospel of John has a significantly different style, vocabulary, and theological focus compared to the three Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke). This suggests a different author and community, writing much later in a distinct context.

- Historical Context: The gospels contain details that scholars argue point to a later date. For example, the detailed descriptions of the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in AD 70 in Matthew, Mark, and Luke suggest that the authors were writing after this event, not before.

-

Why are they still Considered Authoritative?

Despite the scholarly consensus on anonymous authorship and later dating, the gospels are still considered authoritative for several reasons:

-

-

- Apostolic Tradition: The early church didn’t grant authority based solely on who wrote a book, but rather on its connection to apostolic tradition. The traditional authors—Matthew and John (apostles), Mark (a companion of Peter), and Luke (a companion of Paul)—served as a stamp of authenticity. The gospels were accepted because they were believed to be accurate accounts of what the apostles taught and witnessed, regardless of who physically wrote them down.

- Widespread Use and Acceptance: By the late 2nd century, these four gospels were already widely used and accepted across different Christian communities. They had proven their value in worship, teaching, and theological disputes. This “catholicity” or universal acceptance was a key factor in their inclusion in the canon.

- Consistency of Message: Although they differ in style and emphasis, the four gospels present a consistent core message about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. This coherence distinguished them from many other purported gospels, which often presented radically different, and often Gnostic, teachings.

-

Key Non-Canonical Gospels

There were many other gospels in circulation during early Christian history, some of which were quite popular in ancient times and many of which have gained considerable favor among Christians today. These are considered “apocryphal” or “gnostic” and were eventually rejected by the mainstream church.

Gospel of Thomas

Purported Author: Didymos Judas Thomas, the Apostle Thomas.

Date: The date is highly debated. Some scholars argue for an early date (mid-1st century) for an original core of sayings, possibly predating the canonical gospels. Others argue for a later date in the 2nd century, seeing it as dependent on the canonical gospels.

Entered Christian History: The full Coptic text was not discovered until 1945 at Nag Hammadi, Egypt. However, earlier fragments dating to the 2nd century show it was in circulation. Early church fathers like Hippolytus and Origen mentioned and condemned it as heretical.

Gospel of Peter

Purported Author: The Apostle Peter.

Date: Early to mid-2nd century.

Entered Christian History: Only a fragment of this gospel was known to have survived until a larger portion was discovered in the 19th century. Early church fathers like Serapion of Antioch mentioned its use in some communities but ultimately rejected it due to its docetic (Christ did not have a real physical body) theology.

Gospel of Judas

Purported Author: Anonymous, but it portrays Judas Iscariot as a hero who Jesus gave secret knowledge.

Date: Mid-2nd century (c. AD 140–180).

Entered Christian History: Like the Gospel of Thomas, it was lost for centuries and only rediscovered in the 1970s. It was known to early church fathers, as Irenaeus of Lyons mentioned and denounced it around AD 180 as a “fictitious history” used by a Gnostic sect.

Gospel of Mary (Magdalene)

Purported Author: Anonymous, but the main figure is Mary Magdalene.

Date: 2nd century.

Entered Christian History: This Gnostic text was discovered in a 5th-century Coptic papyrus codex. While it was not a narrative gospel of Jesus’s life, it became a significant text in Gnostic circles. It portrays a rivalry between Mary and Peter over who is the true inheritor of Jesus’s secret teachings.

The Diatessaron

Purported Author: Tatian, an Assyrian apologist and ascetic.

Date: C. AD 160-175.

Entered Christian History: This was not a new gospel but a harmony of the four canonical gospels, weaving their texts into a single, continuous narrative. It became the standard gospel text in Syriac-speaking churches for about two centuries until the four separate gospels eventually replaced it. Its widespread use in the late 2nd to 4th centuries is a testament to the early authority of the four gospels it harmonized.

The Original Association

Irenaeus’s argument was a response to Gnostic groups who were circulating their own gospels and challenging the authority of the four books that would become the canonical gospels of the New Testament (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John). He claimed that the four gospels were prefigured in the Old Testament, pointing to Ezekiel’s vision.

He argued that just as there are four cardinal directions and four principal winds, it was fitting that the Church, which is spread throughout the world, should have four foundational gospels. He then connected the four living creatures to different aspects of Christ’s work and each of the gospels:

The Lion: Representing Christ’s royal and powerful nature, he connected this to the Gospel of John because of its focus on the divine and eternal nature of the Word.

The Ox: Symbolizing Christ’s sacrificial and priestly role, it is linked to the Gospel of Luke, which begins with the priest Zacharias.

The Man: Describing Christ’s human advent, he associated this with the Gospel of Matthew due to its focus on Jesus’s genealogy and human birth.

The Eagle: Pointing to the gift of the Spirit descending from on high, he attributed this to the Gospel of Mark because it starts with the prophetic Spirit coming down on men.

Later Changes to the Order

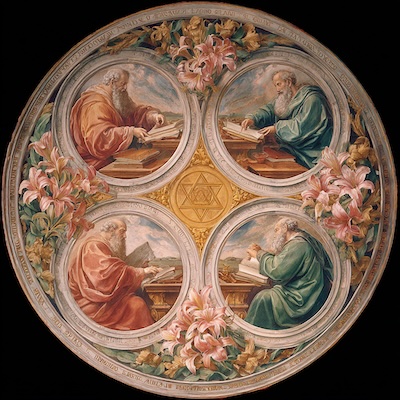

While Irenaeus was the first to make the connection, the specific order he used didn’t become the standard. Over time, different writers adjusted the symbolism. St. Jerome established the most widely accepted and enduring arrangement in the 4th century. This is the association still commonly seen in Christian art and iconography today:

Matthew as the Man or Angel: Because his gospel begins with the human genealogy of Jesus.

Mark as the Lion: Because his gospel starts with the “voice of one crying in the wilderness” (John the Baptist), likened to the roar of a lion.

Luke as the Ox or Calf: Because his gospel begins with the priest Zacharias in the temple, a place of sacrifice, and the ox was a sacrificial animal.12

John as the Eagle: Because his gospel takes a soaring, theological view of Christ’s divinity, beginning with “In the beginning was the Word.”

Conclusion

The story of the four living creatures and the four gospels is more than just a historical curiosity; it is a testament to the providential preservation of the Christian message. In a time of spiritual confusion and competing narratives, Irenaeus, grounded in a direct line of apostolic tradition, provided a clear and compelling argument for a single, consistent, and public gospel. His appeal to the universally accepted four gospels—in contrast to the many fragmented and secretive Gnostic texts—established a critical foundation for Christian orthodoxy. Today, this legacy serves as a powerful reminder that our faith is not based on hidden knowledge or fleeting doctrines, but on the enduring and verifiable person of Jesus Christ as revealed through the four authoritative accounts of His life and ministry.

Call to Action

Reflect on your own faith and its foundation. In a world saturated with information, how do you distinguish between sound doctrine and modern-day gnostic teachings that prioritize intellectual knowledge over a relationship with Christ? Dive deeper into the four canonical gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—and let the consistent, unified message of Jesus Christ serve as your guide.

Discover more from Fathers Heart Ministry

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.